Timing Passes in the Tuamotus

We left Hao on Saturday morning, bound for Raroia. 150 miles pass to pass, probably about a 30 hour sail for us at a 5 knot speed. The amount of time we spent planning this passage might astound any non-sailor, and might even take a few experienced cruisers off guard. What’s the big deal? Fine, you want to arrive in daylight. Noon, maybe? So you leave at 6 am, sail along all day and all night, and you’re exactly where you want to be when you want to be there.

One of our anchorages in Hao

In the Tuamotus, though, you have to take the passes into account. These atolls are like water corrals, with the passes being the only outlet, and the amount of current experienced can sometimes top 7 or 8 knots. Hao has a particularly nasty reputation for excessive current, and Raroia similarly can be a challenge. In an ideal world, you’ll hit a pass at slack current (when there’s no notable current flowing in OR out), but figuring out exactly when slack current might be is such a nuanced thing one of the main tools for doing just that in the Tuamotus is called the “Guesstimator”. It’s not just when high or low tide is (not super easy to understand since there are very few tide stations in the Tuamotus, so many are offset from atolls that might be hundreds of miles away), but also how much the wind has been blowing for how long from what direction, and what kind of swell has been running for how long. A narrow pass that’s the only one for a large atoll might have more current possible than a wide one. You get the idea.

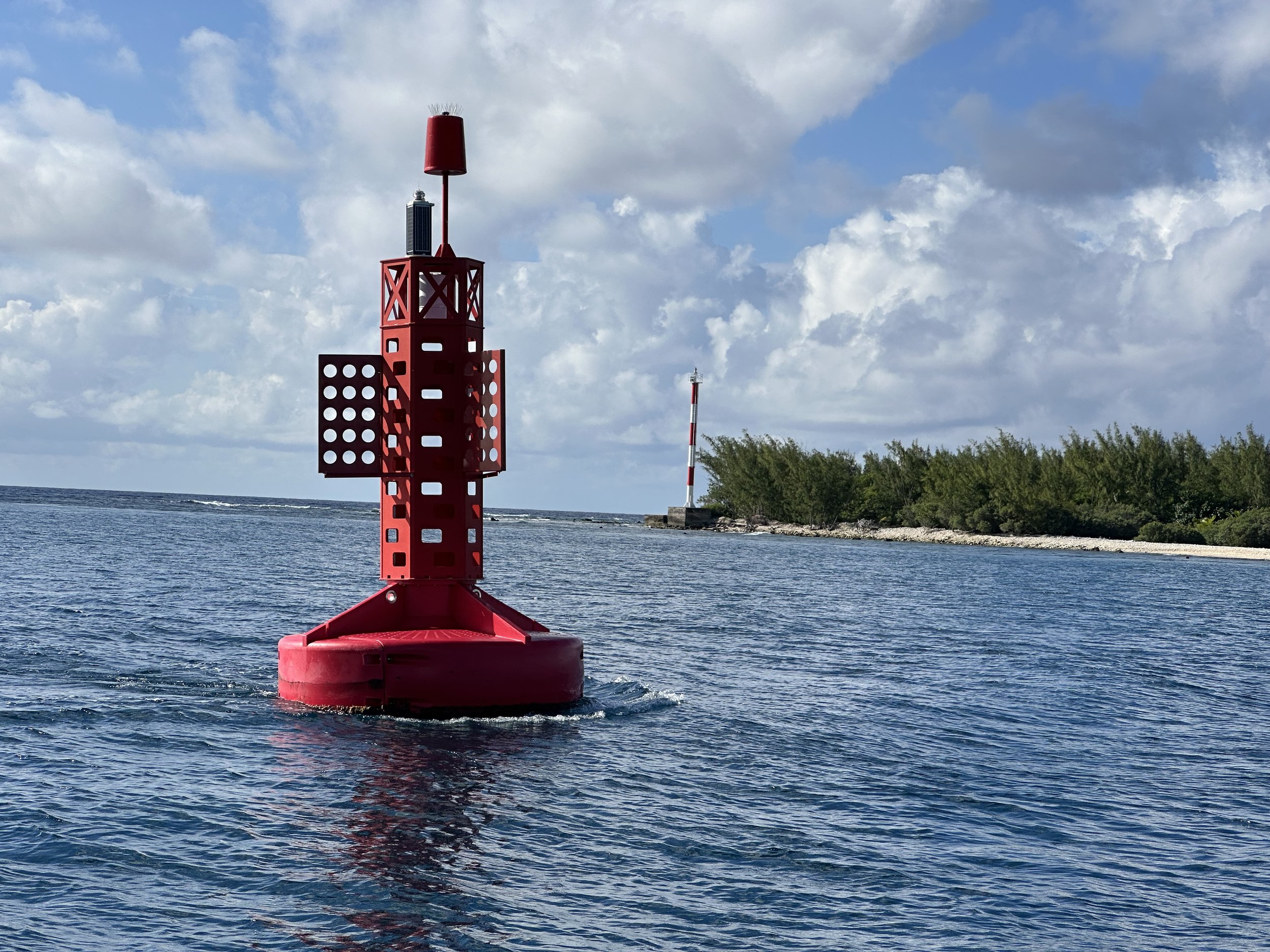

Kaki pass on our entrance. Maybe 4 knots of outgoing current here.

The Kaki pass (Hao) has a reputation for being especially nasty, with Sailing Directions warning that the current can, in the right (wrong!) conditions, approach 12 knots. You can’t move against that, and trying to go WITH it would put your boat at the mercy of the current, with almost no steerage possible. The pass at Raroia isn’t quite as notorious, but people still warn of 5 and 6 knots of current.

Shot from a video of the Kaki pass on our exit. See the fishing boat?

All of a sudden that 150 miles isn’t such an easy thing to calculate. Plus, once we got through the pass at Raroia, we still had another 20 miles or so to get to our anchorage, across a coral-head strewn lagoon that really requires good visibility to navigate safely. Satellite imagery is all well and good but it doesn’t show you everything. Eyeballs in good light are still your very best tool for avoiding the coral. Let’s not forget that we had about 5 miles to traverse from our anchorage at Hao to get to the pass, so good light would be nice for that too.

A coral head, marked with a stick, in the south end of Hao.

Our current thinking on pass management, in the passes we’ve done so far, is to try to time them for high tide. If a good southern swell is running (which seems to be normal this time of year), then the lagoon might never actually be admitting water in through the pass, meaning you might never see a flood current at all but the ebb will be at its least velocity.

High tide at Hao on Saturday? 4:30 am. High tide at Raroia on Sunday? 6 am. Oof.

We’ll eyeball the passes and hope for the best. If there’s a wall of water making the pass impassable (hah, see what I did there?), we’ll just wait until conditions improved.

Sunset in Hao.

We picked up the anchor at first twilight, a little after 5 am on Saturday, following our track out toward the pass. A couple of fishing boats came along right behind us, so we were able to watch them navigate the pass. Swirling water on one side, flat on the other. The current was pulling us out. We went for it. Success!

The actual passage was fast, faster than we’d thought it might be; we were at the pass at Raroia after 160 nautical miles at 9 am. Bumpy lumpy seas made it not especially a comfortable one. Still. Now we were at our next atoll at what we calculated might be the strongest current against us. The pass is a wide one, with a shallow shelf to avoid on the south side. We sailed past the pass to see what we might be dealing with. We were prepared to spend the next few hours tacking back and forth outside the pass if needed. There were rapids visible, but no overfalls. We decided to try, reasoning that we’d be spat right back out long before we reached the shallow area we had to avoid if we couldn’t make it in.

Southern swell breaking on the southern end of Raroia

Sails pulling, engine on and working hard. Speed dropped from 6 knots to 5, then 3, then 2. 1. .5. .23. Still flat water, still able to control the boat. Steadily and VERY VERY VERY slowly we pulled ahead. Our speed hovered at just under a knot; the heading sensor showed us first moving towards land, then into the lagoon, and back again even when the bow was steadily aiming for the northeast. Eddies swirled around us. .5. 1. 1.5. 3. 5.

Eddies swirling as we inch into the lagoon

We were clear.

We calculated that we saw 6 knots or more of current against us as we came in through the pass, in flat water that allowed us to progress in inches.

Google earth image of Raroia. All those dots? Coral heads. We’re anchored in the northeast corner.

By 10 am we were through and heading across the lagoon. By 2 pm, we were anchored in a spot of clear sand about a quarter a mile away from our friends on Vision, who we’d last seen in Panama.

Avoiding coral heads inside the lagoon

Our third atoll, unlocked.

Sunrise over Raroia.